As the movie The Exorcist will show you, demons are a problem to this day. Modern clerics in both the Church of England and the Catholic Church still treat people who believe they’re possessed by demons (for the purposes of this blog I should state that I don’t care whether they really are possessed or not, I write about history not the paranormal).

As the movie The Exorcist will show you, demons are a problem to this day. Modern clerics in both the Church of England and the Catholic Church still treat people who believe they’re possessed by demons (for the purposes of this blog I should state that I don’t care whether they really are possessed or not, I write about history not the paranormal).

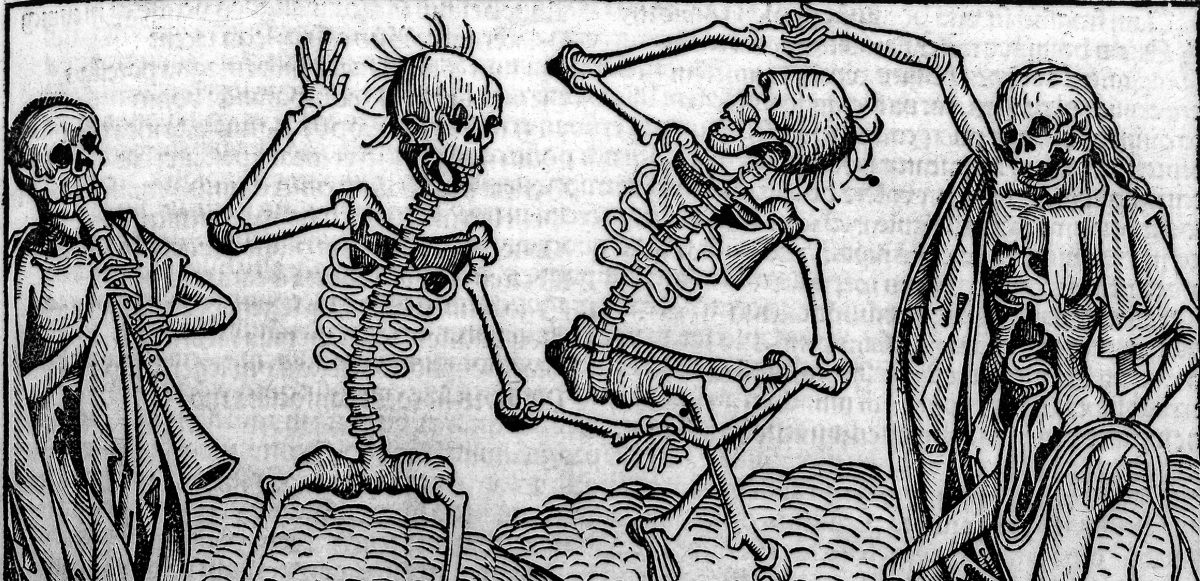

However, demons could be a real problem if you were living in Medieval Europe. In fact, the idea that demons can get you killed is absolutely incontrovertible – in London of 1725 a drunk died of exposure in a well because neighbours ignored his cries for help, believing he was a demon. Not only that, but in 1597 Alice Goodridge, accused of sending a demon to possess Thomas Darling, died in prison awaiting trial for witchcraft.

Interestingly, though, those possessed by demons (demoniacs) occupy a more ambiguous status in the bible. Although John 8.44 describes The Devil as “a liar and the father of lies”, demoniacs in the Gospel were among the first witnesses to Christ, and often showed a clearer understanding of divine truth than the apostles. In fact, Christ himself was accused of being a demon, and of “casting out demons by the prince of demons.”

Literature from the medieval period showed a growing fascination with the demonic, especially verbal duels and other confrontations between clerics or saints and the possessed. Continue reading “Saints Verses Demons: Casting Out the Unholy, and the Possessed as Saints”